I had fun reading about how Julia Ward Howe came to write the Battle Hymn of the Republic on this day in 1861. Really interesting that the song started as a Civil War soldiers’ song, “John Brown’s Body”.

“John Brown’s Body” originated in the 2nd Battalion of the Massachusetts militia. A soldier in the battalion had the same name as the abolitionist who had seized Harper’s Ferry in an effort to raise a slave rebellion, and who was hanged in December 1859.

George Kimball, one of the soldiers, remembered that “we had a jovial Scotchman in the battalion, named John Brown … and as he happened to bear the identical name of the old hero of Harper’s Ferry, he became at once the butt of his comrades. If he made his appearance a few minutes late among the working squad, or was a little tardy in falling into the company line, he was sure to be greeted with such expressions as “Come, old fellow, you ought to be at it if you are going to help us free the slaves”…

…or, “This can’t be John Brown—why, John Brown is dead.” And then some wag would add, in a solemn, drawling tone, as if it were his purpose to give particular emphasis to the fact that John Brown was really, actually dead: “Yes, yes, poor old John Brown is dead; his body lies mouldering in the grave.”

Typical soldier humor, right? These jokes and sayings were compiled into a song which then gained popularity among other units. Kimball added,

“Finally ditties composed of the most nonsensical, doggerel rhymes, setting for the fact that John Brown was dead and that his body was undergoing the process of dissolution, began to be sung to the music of the hymn above given. These ditties underwent various ramifications, until eventually the lines were reached…

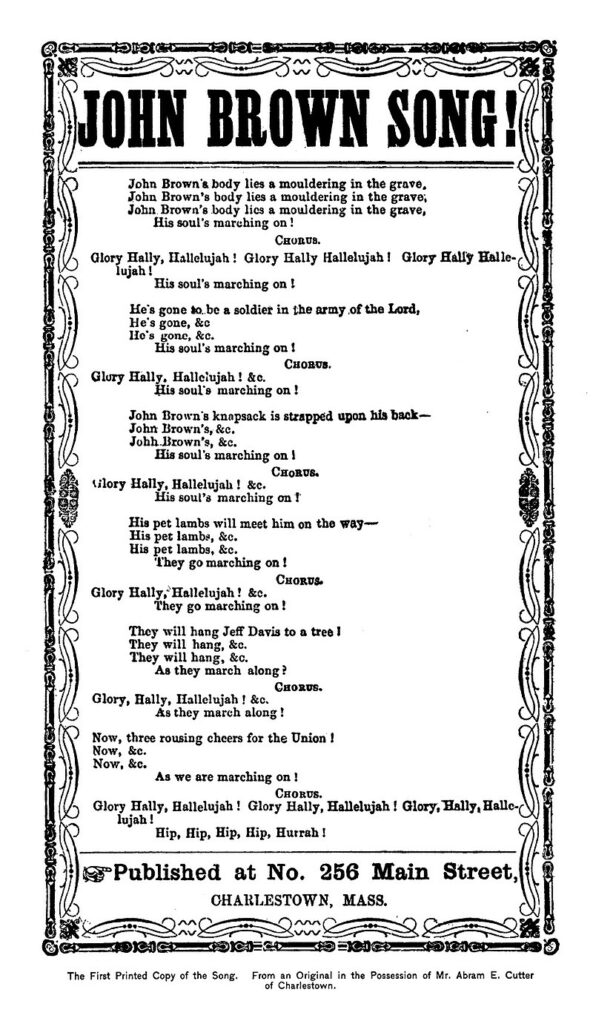

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

His soul’s marching on.

And,—

He’s gone to be a soldier in the army of the Lord,

His soul’s marching on….”

The song was printed and then probably played formally for the first time on May 12, 1861 at a flag raising ceremony at Fort warren in Boston. Soon, printers everywhere were selling copies of the song, riding the wave of northern patriotic fever at the start of the Civil War.

Now, when you read the lyrics, they are a bit gross. Remember, it’s soldier humor, talking about John Brown’s body decomposing and how he has gone to be “a soldier in the Army of the Lord.” Inevitably, some officers tried to stifle the song, which of course only made it more popular.

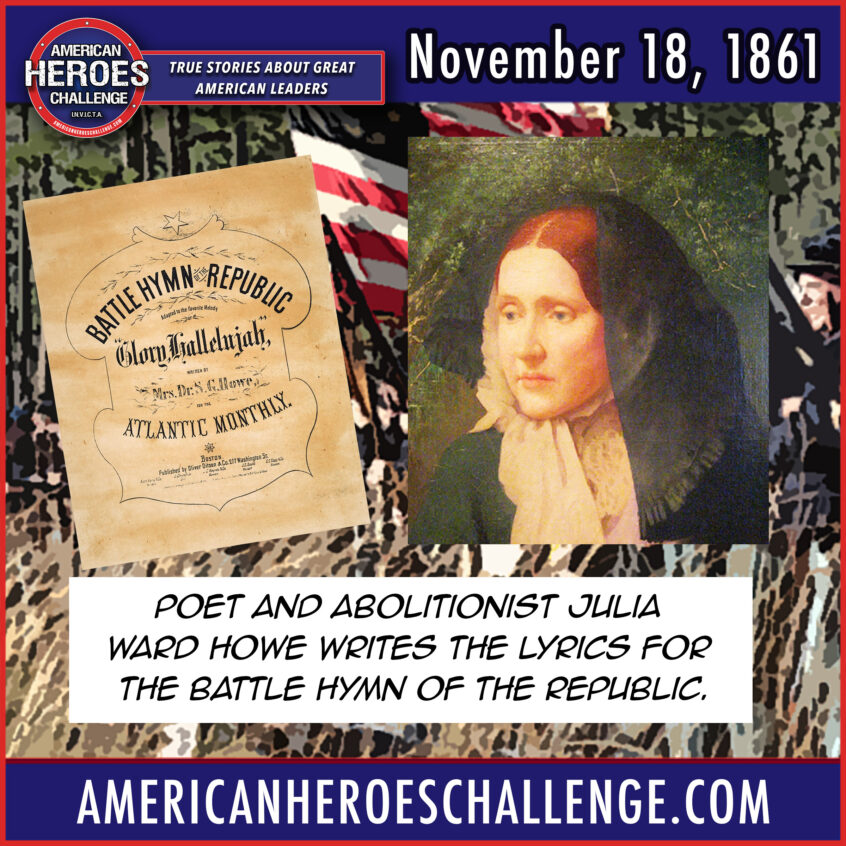

Enter Julia Ward Howe, a member of the New York elite, related by family to Francis “The Swamp Fox” Marion and to the Astors by marriage. Connected and educated, her dad was a successful banker and she published poetry, traveled to Cuba and was a strong abolitionist.

Howe’s life is fascinating and worth checking out. She hard “John Brown’s Body” at a troop review outside Washington DC in November 1861, and her companion, Reverend James Freeman Clarke, suggested that she write new lyrics for the tune. Totally unclear to me if he and Howe disapproved of the original song, or if they were inspired by it. Regardless, Howe wrote the new song the next morning at the Willard Hotel, the famous establishment right across from White House.

“I went to bed that night as usual, and slept, according to my wont, quite soundly. I awoke in the gray of the morning twilight; and as I lay waiting for the dawn, the long lines of the desired poem began to twine themselves in my mind. Having thought out all the stanzas, I said to myself, “I must get up and write these verses down, lest I fall asleep again and forget them.” So, with a sudden effort, I sprang out of bed, and found in the dimness an old stump of a pencil which I remembered to have used the day before. I scrawled the verses almost without looking at the paper.”

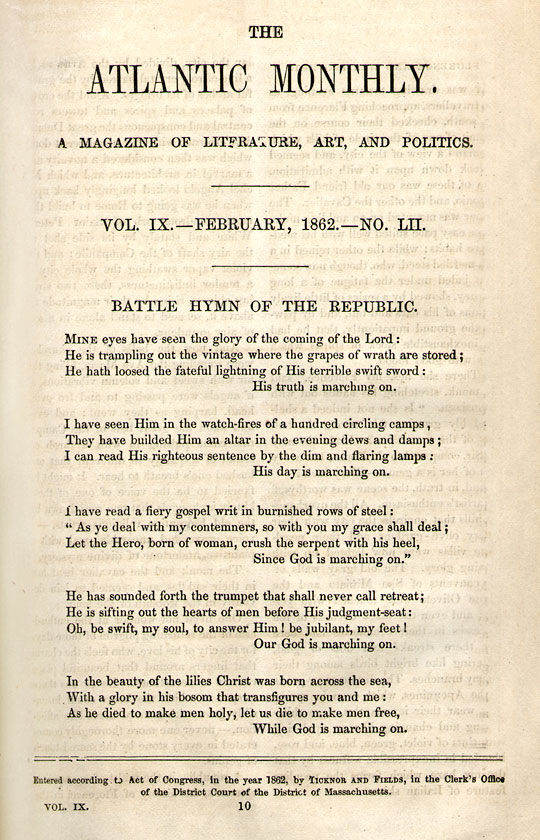

The Atlantic Monthly printed the new song in February 1862, and it quickly famously and widely played. It’s an incredible and stirring piece of music. Honor and remember Julia Ward Howe and all those who fought to preserve the Union.